Residents of South Minneapolis, Richfield, and Bloomington got some very bad news last week. In response to a move by Dakota County to leave the Counties Transit Improvement Board, CTIB is considering withdrawing its funding for the Orange Line Bus Rapid Transit. The Orange Line would be the metro’s first true bus rapid transit line, offering similar frequency to and better transit time than our Light Rail lines. Unlike our light rail lines, however, the Orange Line will cost only about $150 million — less than 1/1o the cost of Southwest LRT.

Although end-to-end, the line connects Dakota County to downtown Minneapolis, the vast majority of the capital investment, stops, and riders are within Hennepin County. Although I do not agree with Dakota County’s decision to leave CTIB, I am outraged that the CTIB board is playing political games with a much-needed, cost-effective transit line that will serve my community.

The Orange Line

The Orange Line would run along the 35W corridor from downtown Minneapolis, through South Minneapolis, Richfield, and Bloomington — each getting two stops — and terminating in Burnsville. A future extension is contemplated to Lakeville, but not included as part of this project.

Within the 494 beltway, the Orange Line is similar to the 535 bus line — however, the Orange Line will vastly improve on the 535, with improved frequency, station experience, and ride quality. Like the “A” line and LRT, the Orange Line will have off-board payment and ticket machines available at every station.

Infrastructure Improvements for Hennepin County

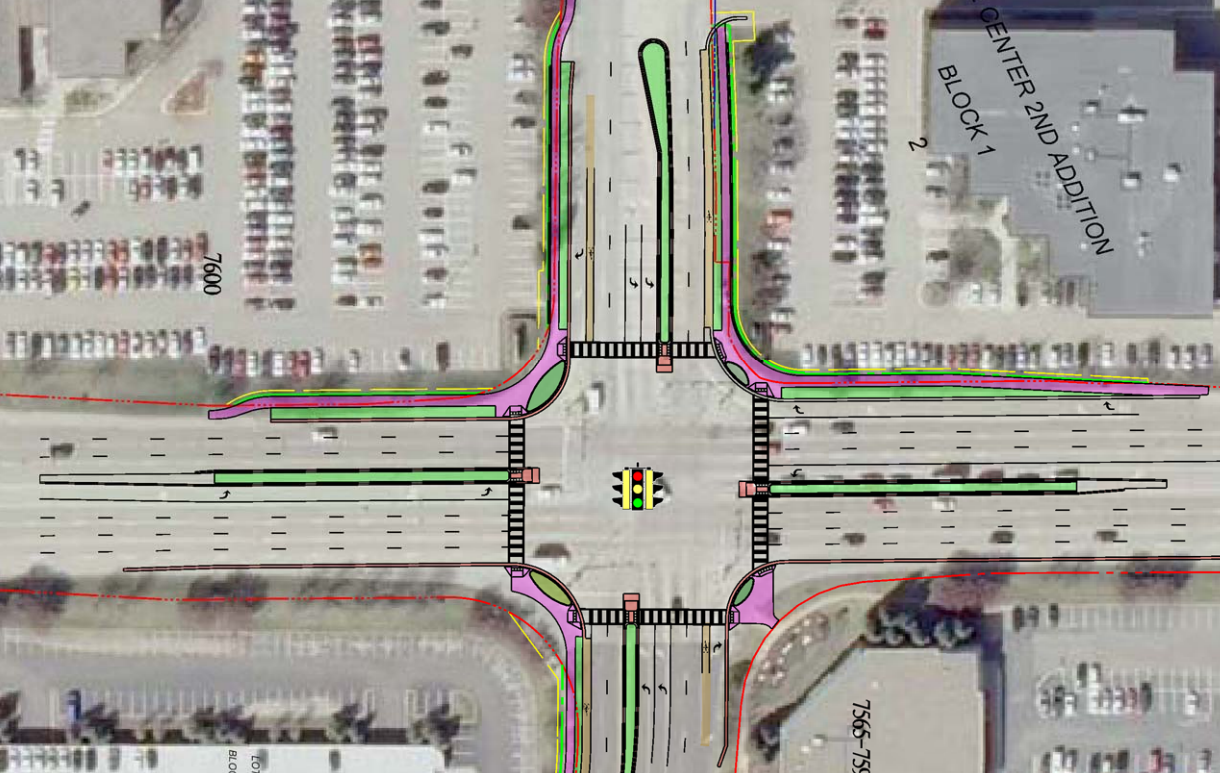

The capital improvements being done as part of the line will also significantly improve the speed and reliability of the ride, for both the Orange Line and other express buses. Lake Street Station will be rebuilt to a high-quality, accessible, sheltered station that will allow buses to pick up and drop off customers without having to cross five lanes of rush-hour traffic. At 494, the bus will exit 35W and go through a new underpass between a 76th St Station (serving offices of Best Buy and US Bank) and American Blvd Station (serving the Southtown and Penn-American District). The underpass will also provide an essential bike-ped connection where there is currently a one-mile gap between crossings.

“A Dakota County Nexus”

In the presentation at the last CTIB meeting, the Orange Line funding was listed alongside projects benefitting solely Dakota County — like a rebuild of the Cedar Grove Transit Station. I was surprised to see the Orange Line framed as a Dakota County project — in part because I, myself, had planned to use it to go from Richfield to downtown, and in part because the majority of the stops and improvements are clearly within Hennepin County.

I spoke with Christina Morrison, the Metro Transit project manager for the Orange Line. According to Morrison, 92% of the 2040 Orange Line boardings are anticipated to be from Hennepin County. This is overwhelmingly a project that will serve Hennepin County residents and businesses.

What’s more, according to Morrison, CTIB’s $45 million contribution would come from the years 2016, 2017, and 2018 — and Dakota County’s payments to CTIB would not terminate until the end of 2018. Even with their withdrawal, Dakota County would still be paying their fair share toward this project.

Time to Act

CTIB will decide whether to move forward with Orange Line funding at their August meeting. I strongly encourage you to to contact your CTIB representatives to express your support for the project. For Hennepin County, those representatives are Peter McLaughlin <[email protected]> and Mike Opat <[email protected]>.

The Orange Line is an important, cost-effective project that will make 35W functional for all-day transit service. And residents of Hennepin County should not be punished, simply because they are on the way to Burnsville.

Edina, Minn — The City of Edina today announced ambitious plans to rebrand the aging Southdale District as “Stroaddale”, and to establish strict historic preservation guidelines to ensure that its low-density, stroad-oriented development is cherished for future generations. Stroaddale District is named for Stroaddale Center, and is roughly bounded by Crosstown to the north, Valley View Stroad to the west, 494/5 to the south, and Xerxes Avenue to the east.

Edina, Minn — The City of Edina today announced ambitious plans to rebrand the aging Southdale District as “Stroaddale”, and to establish strict historic preservation guidelines to ensure that its low-density, stroad-oriented development is cherished for future generations. Stroaddale District is named for Stroaddale Center, and is roughly bounded by Crosstown to the north, Valley View Stroad to the west, 494/5 to the south, and Xerxes Avenue to the east.