Last spring, at a voter forum for Richfield’s west-side City Council seat, there were a number of questions about the mid-century commercial development that lines Penn Avenue between the Crosstown and 68th Street. Voters and candidates spoke of “tired” buildings, non-conforming sites, and inadequate parking. These questions about Penn Avenue seem to come up in every election cycle, and our elected officials are often put on the defense of why there continue to be vacant storefronts, and almost no major redevelopment.

The longer I’ve lived in Richfield, and the more deeply I’ve become involved in conversations around development, the more I have come to realize something: yes, Penn Avenue has all of those “problems.” But many aren’t problems at all. They’re what makes this corridor the best hub of small business in Richfield. And there are better ways to make this area even better.

Meet Penn Central

Immediately south of Crosstown Highway, Penn Avenue is true mix of styles and types of businesses. The massive parking lot of the Lunds store is the first thing you’ll see on the west, while the east side is littered with independent small businesses, ranging from Woof Central doggy daycare to Johnston’s Vac and Sew to one of only two classic barber shops in the city. Around the corner at 66th, you’ll find Aida, one of my favorite restaurants in the city.

The distinctive small business district has an informal business association, and has branded their neighborhood as Penn Central. This organization, together with the City, hosts Richfield’s annual Open Streets festival, PennFest.

The fact that small business is concentrated on Penn is no accident: these “tired” buildings on small lots are affordable and accessible to small businesses. As a planning commissioner, I have often heard residents share concerns that new development only brings more chains to the community. This, also, is no accident: chains can afford higher rent, and have more specific requirements for their building that are easier to do with new construction.

Cities do not have the right to control if a chain or small business is allowed to occupy a building — but we do make a choice in terms of what environment we want to create. Replacing affordable older buildings with brand-new buildings will have the effect of displacing small business and attracting more national chains. That may be inevitable, but it does not have to be a process we help accelerate.

The Penn Avenue Guidelines are the wrong solution to a problem that doesn’t exist

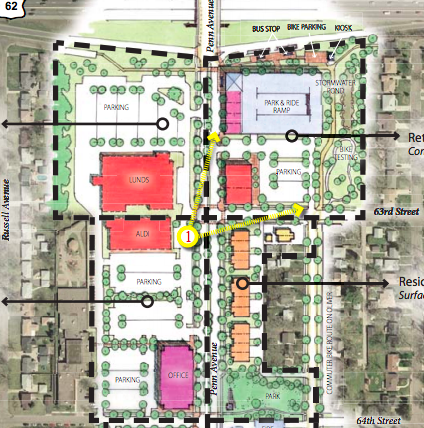

In 2008, in response to ongoing desires to improve the Penn corridor, the City contracted with an outside consultant to create a new master plan for the area. This process was valuable, and has given us a rigorous, high-quality zoning code for the area, that includes important features to improve the pedestrian environment, ensure high-quality development, and to limit uses that detract from the neighboring properties, like auto sales and drive-thrus.

However, the big picture proposed by the plan is disturbing. In a hypothetical redevelopment scenario, the plan envisions every single unit of small, affordable space for small business being eliminated — replaced by larger, mixed-use buildings. Even worse: the plan envisions every single piece of existing naturally occurring affordable housing being replaced.

This is not a good end-goal to have — if we were “successful”, we would eliminate important parts of our local economy, and the exciting, interesting businesses that help make Richfield a great place to live.

With no problem to solve, we don’t need to be desperate

The first project proposed after the Penn Avenue plan was a CVS Pharmacy. This project went against many of the principles of the plan: it was large, single-use retail. Facing the sidewalk, it didn’t offer the customer entrances, display windows, and awnings envisioned — instead it had a large, blank retaining wall, which allowed the parking lot to loom over Penn Avenue. But it was approved, feeling that demonstrating some sign of life would help inspire additional redevelopment.

Since that building was built six years ago, there has been no new construction on the corridor, although most existing businesses continue to thrive. Now, the City is considering an application for the first new development proposed in years: a fast food restaurant. Like CVS, this would be another single-use chain, this time with half the required density, and with a drive-thru speaker that is half the required distance to housing.

The Planning Commission, on which I serve, voted against the variances that would allow this fast-food restaurant to build — although it remains to be seen if the City Council will accept or overrule that recommendation. The problems with the development are significant, and it was clear to me as a planning commissioner that they did not meet the specific standards for the variances they were seeking.

In the bigger picture, developments like this fast food restaurant offer little to the community. They are certainly not the high-intensity development that the Penn Avenue Guidelines envision. Occupying a tiny portion of the site, they do not offer much improvement to the tax base. They have significant externalities in terms of noise, air pollution, and traffic. And they replace more-affordable commercial property with less-affordable new development.

How to fix Penn Avenue? Fix Penn Avenue.

Although it offers a lot to the community, there are admittedly problems on Penn: some spaces remain persistently vacant, and the cosmetic appearance of the corridor is poor. If we want to improve the appearance of the corridor, let’s start with something that doesn’t have to cost businesses a dime, and something that we can do right away: rebuild Penn Avenue.

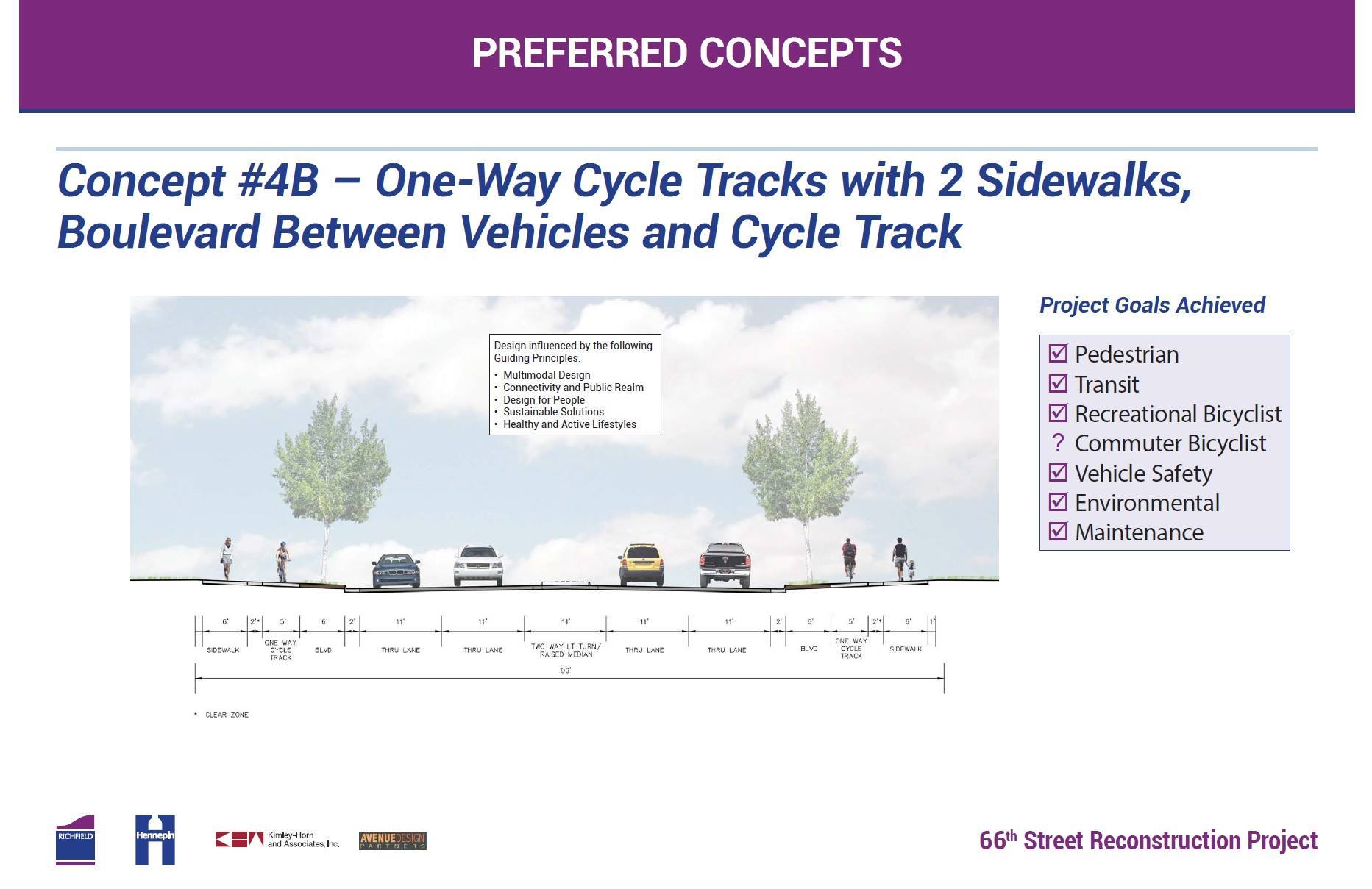

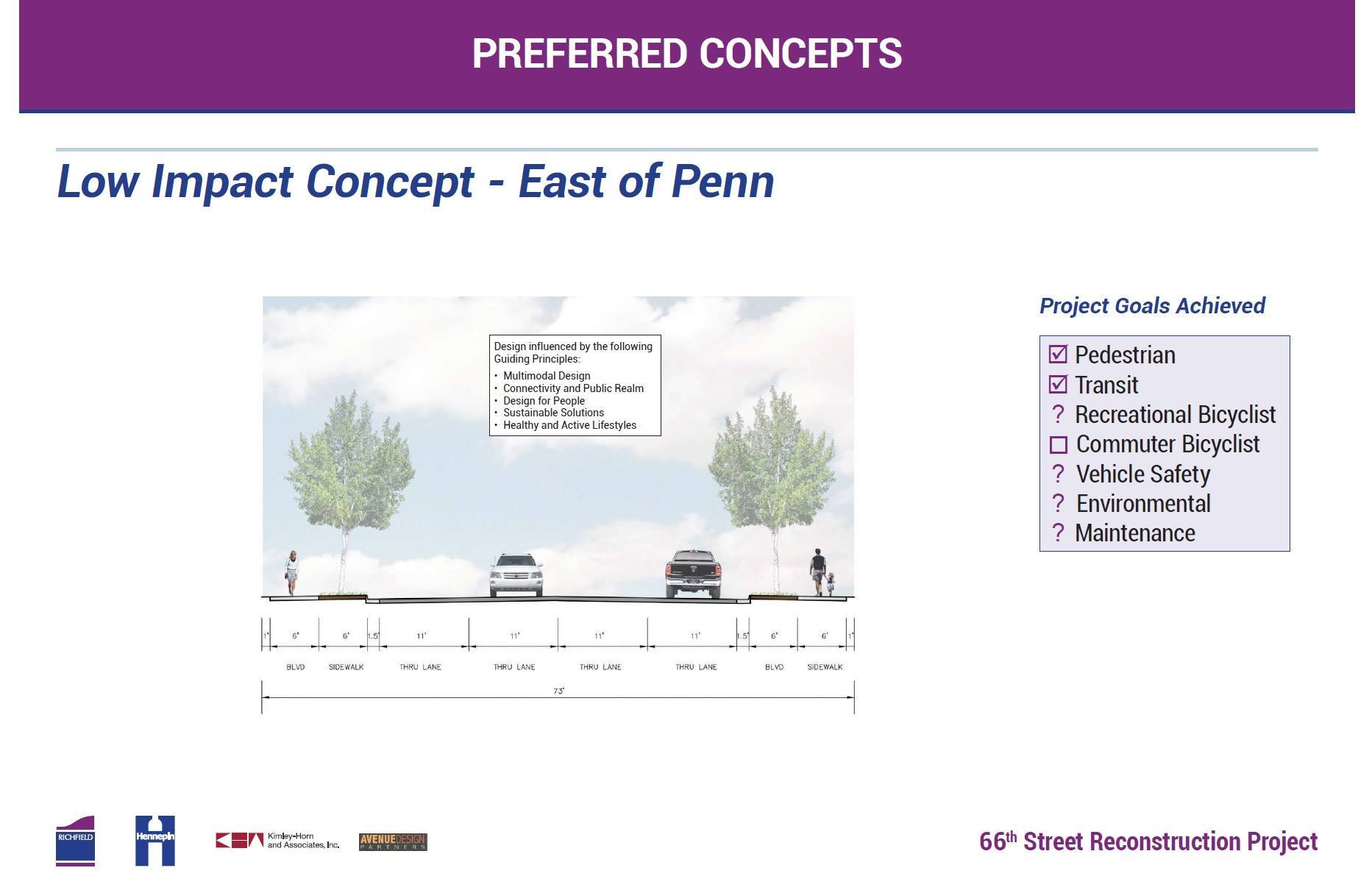

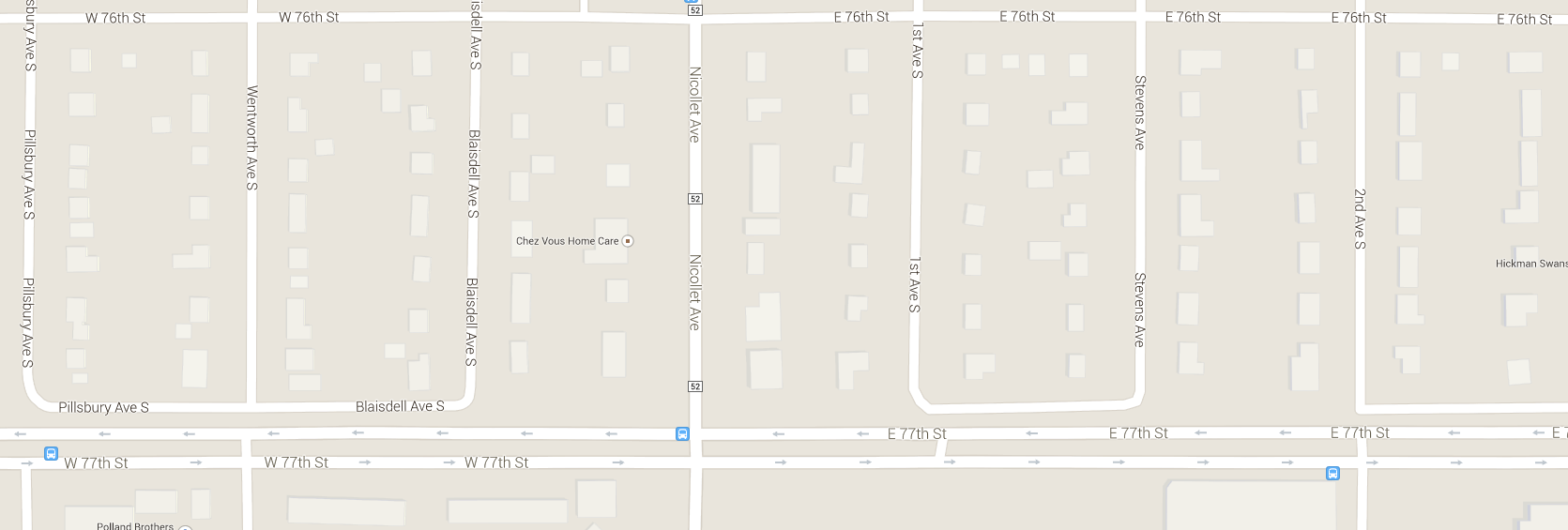

The four-lane death road, owned by Hennepin County, is a grim relic of yesterday’s engineering. Sidewalks are completely inaccessible. Speeding is common. On-street parking that could serve businesses exists for only a single block. Crossing from one side of the street to another — a key component of a walkable business district — is all but impossible.

Let’s not eliminate our small business corridor. Let’s help it thrive, by giving businesses an attractive home, and giving their customers and our residents a safe place to walk, shop, and live.