Note: this is from my personal perspective as a Richfielder and a supporter of the new 66th. It is not City of Richfield communication.

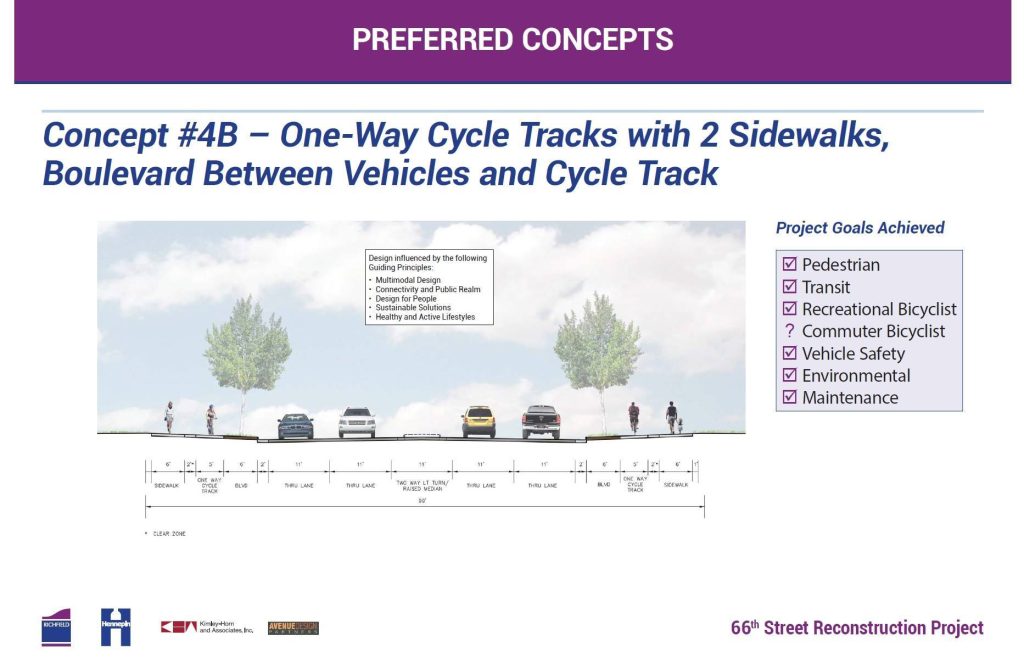

From 2016 to 2018, Richfield and Hennepin County rebuilt 66th Street, Richfield’s main street. The project was the most ambitious rebuild of an arterial Richfield had ever undertaken, and set precedent for the region — the first example of an extensive use of a sidewalk-level, one-way protected bikeway.

This design has been used in other cities since, and a similar design was selected for the 2026 rebuild of Nicollet Avenue in Richfield.

The project rebuilt 66th from Xerxes Avenue to 16th Avenue (near Cedar). Unfortunately, a small gap area around Portland Avenue was omitted from the project, creating a discontinuity for cyclists and pedestrians.

Before and after the rebuild, I took dozens of pictures of the conditions of the street, which I’m sharing now for easy comparison.

Before and After

16th Avenue to Nicollet Avenue

East of Nicollet Avenue, a 2/3-lane design was used. Medians were prioritized in the area of Veterans Park and the neighborhood to the west.

This area previously had a lot of unimproved right-of-way, which was better-utilized after the rebuild. Some additional right-of-way was also acquired.

66th Street and 15th Ave: Looking west from the center line.

66th Street and 10th Ave: Looking west

66th Street and 3rd Ave S, as seen from the sidewalk. Utility lines running along 66th were buried as part of the project.

66th Street and 2nd Ave S, as seen from the center line. A mix of center turn lanes and medians were used in this section.

66th Street and 2nd Ave S, as seen from the sidewalk. The center line shifted north to use previously unimproved right-of-way.

66th Street and Stevens Avenue. Although crossing conditions have improved, this intersection like most lacks marked crosswalks.

66th Street and 1st Ave

Downtown Richfield — Nicollet Avenue to I-35W

West of Nicollet Avenue, a divided 4/5-lane design was used. Note the significant change at Nicollet and Lyndale, where signals were replaced with roundabouts.

66th and Nicollet roundabout

66th and Nicollet looking west by Academy of Holy Angels.

66th and Lyndale looking west: Signal replaced with roundabout, and protected bikeway and green space added.

66th and Lyndale looking east: Signal replaced with roundabout, and protected bikeway and green space added.

66th just west of Lyndale: Looking west from the sidewalk.

66th near Woodlake Drive: Looking west from middle of the roadway. Note the increased green space behind the curbs, as well as the median.

66th & 35W: Looking west on the north side sidewalk. Unfortunately, the right-turn lane was retained, which makes this transit location less pedestrian-friendly.

66th & 35W: Looking west on the south side sidewalk

66th & 35W: Under the bridge. The bridge was not rebuilt as part of this project, but the sidewalks were reconstructed to widen them and add the protected bike lane.

West of 35W

A divided 4/5 lane was used from 35W to Penn. In this section, 18 homes had to be removed to provide adequate right-of-way for the new street. This was by far the most controversial decision of the rebuild of 66th.

West of Penn, because the road had already been widened in the 1980s, a compromise with the neighborhood agreed to contain the new street within the existing right-of-way.

Unfortunately, the county prioritized maximizing car capacity over providing a dedicated bicycle facility in this section. As a result, the bicycle facility ends at Penn/Oliver Avenue. (West of Penn, the north side sidewalk is widened slightly from standard and serves as an 8′ sidepath to provide a limited off-street option for bikes.)

I took my before pictures in 2017, and so I did not capture this section personally before construction began. Instead, I am providing Google Street View imagery of a few key locations.

66th and James Avenue in 2014 and 2023. Note the homes that were removed to the left, on the south side. One benefit at this particular intersection was providing much better access to Monroe Park, which was previously hidden behind the houses. Imagery: Google Street View.

66th and Logan Avenue in 2014 and 2023. Signals along 66th attempted to use the protected intersection concept, although in an effort to reduce right-of-way needs, the intended effect wasn’t really achieved. For example, bicycles aren’t detected going north-south here, so a cyclist must go over to the sidewalk and press the pedestrian push button anyway. Imagery: Google Street View.

66th and Sheridan Avenue in 2014 and 2023. This was the section where right-of-way was limited, and the county prioritized additional car capacity over continuing the bicycle facility. Still, a boulevard was added, as well as improved lighting. Imagery: Google Street View.

After about an hour of testimony from residents, county engineer Carla Stueve gave some initial responses. Although she offered some welcome suggestions (bumpouts using plastic flex post delineators, turn restrictions), she immediately discounted the most significant tool that could improve Lyndale in the near term: a 4-to-3 conversion. This, she said, could only be done under a reconstruction but the county would “consider” this feedback at that time.

After about an hour of testimony from residents, county engineer Carla Stueve gave some initial responses. Although she offered some welcome suggestions (bumpouts using plastic flex post delineators, turn restrictions), she immediately discounted the most significant tool that could improve Lyndale in the near term: a 4-to-3 conversion. This, she said, could only be done under a reconstruction but the county would “consider” this feedback at that time.